![Never Let Me Go (Vintage International) 石黑一雄:彆讓我走 2017諾貝爾文學奬得主作品 [平裝]](https://pic.windowsfront.com/19045218/rBEhWlJT39kIAAAAAAoPpfGK8A8AAD56AE2-ScACg-9036.jpg)

具體描述

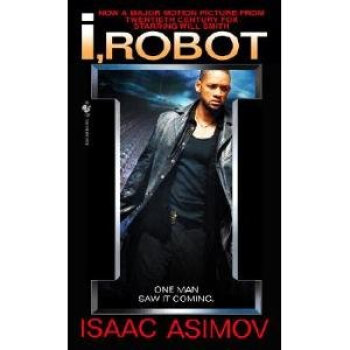

編輯推薦

布剋奬提名、歐洲文學奬得主From The Washington Post

Kazuo Ishiguro's strange, and strangely affecting, new novel revolves around three people whom we first meet as children and whose fates are decided in early adulthood. It is an exceedingly difficult novel to review because essential aspects of it are also essential to the complex mystery at its core, so discussing it almost immediately becomes a delicate balance between what can and cannot be revealed. Believing as I strongly do that readers must be allowed to discover a book's secrets for themselves, guided by the author's hand, rather than have those secrets gratuitously spilled by a reviewer, I shall err on the side of silence, so please bear with me.

Never Let Me Go is set in an undisclosed time -- not in the future, though the novel pays more than a slight bow to science fiction, perhaps between the 1950s and the 1970s -- at a place in the British countryside called Hailsham. It is a school, but a school unlike any other. It was intended to be "a shining beacon, an example of how we might move to a more humane and better way of doing things." The teachers are called "guardians" and the students, though that is what they are called, are neither ordinary students nor ordinary children. They come to Hailsham at a very early age and stay there until, as older teenagers, they are permitted to live in "the Cottages" or "the White Mansion" or "Poplar Farm," halfway houses from which they make tentative steps into the real world.

The narrator of the novel is Kathy, or Kath, and the two other principal characters are her close friends and occasional rivals, Ruth and Tommy. She is "thirty-one years old, and . . . a carer now for over eleven years." What is a carer? One of the novel's mysteries, not really to be solved until two-thirds of the way through; suffice it to say that it's a difficult, emotionally and physically wearing job. Ruth and Tommy, approximately her own age, are "donors," but that mystery, too, must be left to Ishiguro to solve.

In any event, for most of the novel Ishiguro is primarily concerned with the three as children and with the odd world they inhabit at Hailsham. The school, or institution, or whatever one cares to call it, is located on a large parcel of beautiful land, isolated from the outer world. Its students are made to understand that "we were all very special," that "we were different from our guardians, and also from the normal people outside." Their futures are hinted at but not faced head-on: "We hated the way our guardians, usually so on top of everything, became so awkward whenever we came near this territory. It unnerved us to see them change like that." They have a "special chance," but they have only the vaguest idea what that might be.

They are so caught up in the rituals and routines of Hailsham, though, that they have little time for speculation about the distant time of adulthood. They excitedly await "Exchanges," for example: "Four times a year -- spring, summer, autumn, winter -- we had a kind of big exhibition-cum-sale of all the things we'd been creating in the three months since the last Exchange. Paintings, drawings, pottery; all sorts of 'sculptures' made from whatever was the craze of the day -- bashed-up cans, maybe, or bottle tops stuck onto cardboard." Each child is given "Exchange Tokens" with which he or she can "buy work done by students in your own year," from which they form collections that become precious mementos of their time at Hailsham.

The very best products of their creative labors go to "the Gallery." None of them has ever seen it or even knows where it is, but the pieces for it are regularly chosen by a woman whose name they do not know -- "we called her 'Madame' because she was French or Belgian -- there was a dispute as to which -- and that was what the guardians always called her" -- and having one's work selected is regarded as a great honor. They also know that Miss Emily, the head of Hailsham, told one student "that things like pictures, poetry, all that kind of stuff, she said they revealed what you were like inside. She said they revealed your soul."

Besides the Exchanges, the children look forward to the Sales, which "were important to us because that was how we got hold of things from outside." Every month "a big white van" brings the flotsam and jetsam of the outside world:

"Looking back now, it's funny to think we got so worked up, because usually the Sales were a big disappointment. There'd be nothing remotely special and we'd spend our tokens just renewing stuff that was wearing out or broken with more of the same. But the point was, I suppose, we'd all of us in the past found something special at a Sale, something that had become special: a jacket, a watch, a pair of craft scissors never used but kept proudly next to a bed. We'd all found something like that at one time, and so however much we tried to pretend otherwise, we couldn't ever shake off the old feelings of hope and excitement."

Too, the Sales are a way of connecting to the world outside: "at that stage in our lives, any place beyond Hailsham was like a fantasy land; we had only the haziest notions of the world outside and about what was and wasn't possible there." Hailsham is a closed circle beyond which they are not permitted to venture, with the result that the larger world becomes the subject of apprehension as well as curiosity: The children are "fearful of the world around us, and -- no matter how much we despised ourselves for it -- unable quite to let each other go."

That theme, which recurs throughout the book, is summarized for Kathy by a long-playing record she owned for a while -- eventually, and mysteriously, it vanished -- called "Songs After Dark," by a singer named Judy Bridgewater (fictitious, as best I can determine), one track of which is a song titled "Never Let Me Go." The students have been told "it was completely impossible for any of us to have babies," but even as a very young child Kathy dreams of having one:

"What was so special about this song? Well, the thing was, I didn't used to listen properly to the words; I just waited for that bit that went: 'Baby, baby, never let me go. . . .' And what I'd imagined was a woman who'd been told she couldn't have babies, who'd really, really wanted them all her life. Then there's a sort of miracle and she has a baby, and she holds this baby very close to her and walks around singing: 'Baby, never let me go. . .' partly because she's so happy, but also because she's so afraid something will happen, that the baby will get ill or be taken away from her. Even at the time, I realized this couldn't be right, that this interpretation didn't fit with the rest of the lyrics. But that wasn't an issue with me. The song was about what I said, and I used to listen to it again and again, on my own, whenever I got the chance."

One time Kathy is alone in her room, playing the song, "swaying about slowly in time to the song, holding an imaginary baby to my breast." Then "something made me realize I wasn't alone, and I opened my eyes to find myself staring at Madame framed in the doorway. . . . She was out in the corridor, standing very still, her head angled to one side to give her a view of what I was doing inside. And the odd thing was she was crying. It might even have been one of her sobs that had come through the song to jerk me out of my dream." When she tells Tommy about this, he says: "Maybe Madame can read minds. She's strange. Maybe she can see right inside you."

What Madame thinks she sees will not be revealed for many pages, but it gets right to the essence of this quite wonderful novel, the best Ishiguro has written since the sublime The Remains of the Day. It is almost literally a novel about humanity: what constitutes it, what it means, how it can be honored or denied. These little children, and the adults they eventually become, are brought up to serve humanity in the most astonishing and selfless ways, and the humanity they achieve in so doing makes us realize that in a new world the word must be redefined. Ishiguro pulls the reader along to that understanding at a steady, insistent pace. If the guardians at Hailsham "timed very carefully and deliberately everything they told us, so that we were always just too young to understand properly the latest piece of information," by the same token Ishiguro carefully and deliberately unfolds Hailsham's secrets one by one, piece by piece, as if he were slowly peeling an artichoke.

內容簡介

From the Booker Prize-winning author of The Remains of the Day comes a devastating new novel of innocence, knowledge, and loss. As children Kathy, Ruth, and Tommy were students at Hailsham, an exclusive boarding school secluded in the English countryside. It was a place of mercurial cliques and mysterious rules where teachers were constantly reminding their charges of how special they were. Now, years later, Kathy is a young woman. Ruth and Tommy have reentered her life. And for the first time she is beginning to look back at their shared past and understand just what it is that makes them special–and how that gift will shape the rest of their time together. Suspenseful, moving, beautifully atmospheric, Never Let Me Go is another classic by the author of The Remains of the Day.作者簡介

Kazuo Ishiguro is the author of five previous novels, including The Remains of the Day, which won the Booker Prize and became an international best seller. His work has been translated into twenty-eight languages. In 1995 he received an Order of the British Empire for service to literature, and in 1998 was named a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French government. He lives in London with his wife and daughter.石黑一雄,著名日裔英國小說傢。曾獲得瞭在英語文學裏享有盛譽的“布剋奬”。他的文體以細膩優美著稱,幾乎每部小說都被提名或得奬,其作品已被翻譯成二十八種語言。

所獲奬項:

1989年,石黑一雄獲得瞭在英語文學裏享有盛譽的“布剋奬”。石黑一雄的文體以細膩優美著稱,幾乎每部小說都被提名或得奬,其作品已被翻譯成二十八種語言。

石黑一雄年輕時即享譽世界文壇,與魯西迪、奈波爾被稱為“英國文壇移民三雄”,以“國際主義作傢”自稱。曾被英國皇室授勛為文學騎士,並獲授法國藝術文學騎士勛章。

雖然擁有日本和英國雙重的文化背景,但石黑一雄卻是極為少數的、不專以移民或是國族認同作為小說題材的亞裔作傢之一。即使評論傢們總是想方設法,試圖從他的小說中找尋齣日本文化的神髓,或是耙梳齣後殖民理論的蛛絲馬跡,但事實上,石黑一雄本人從來不刻意去操作亞裔的族群認同,而更以身為一個國際主義的作傢來自詡。

對石黑一雄而言,小說乃是一個國際化的文學載體,而在一個日益全球化的現代世界中,要如何纔能突破地域的疆界,寫齣一本對於生活在任何一個文化背景之下的人們,都能夠産生意義的小說,纔是他一嚮努力的目標。因此,石黑一雄與並稱為“英國文壇移民三雄”的魯西迪、奈波爾相比,便顯得大不相同瞭。

精彩書評

"A page turner and a heartbreaker, a tour de force of knotted tension and buried anguish.” —Time“A Gothic tour de force. . . . A tight, deftly controlled story . . . . Just as accomplished [as The Remains of the Day] and, in a very different way, just as melancholy and alarming.” —The New York Times

"Elegaic, deceptively lovely. . . . As always, Ishiguro pulls you under." —Newsweek

“Superbly unsettling, impeccably controlled . . . . The book’s irresistible power comes from Ishiguro’s matchless ability to expose its dark heart in careful increments.” —Entertainment Weekly

前言/序言

My name is Kathy H. I’m thirty-one years old, and I’ve been a carer now for over eleven years. That sounds long enough, I know, but actually they want me to go on for another eight months, until the end of this year. That’ll make it almost exactly twelve years. Now I know my being a carer so long isn’t necessarily because they think I’m fantastic at what I do. There are some really good carers who’ve been told to stop after just two or three years. And I can think of one carer at least who went on for all of fourteen years despite being a complete waste of space. So I’m not trying to boast. But then I do know for a fact they’ve been pleased with my work, and by and large, I have too. My donors have always tended to do much better than expected. Their recovery times have been impressive, and hardly any of them have been classified as “agitated,” even before fourth donation. Okay, maybe I am boasting now. But it means a lot to me, being able to do my work well, especially that bit about my donors staying “calm.” I’ve developed a kind of instinct around donors. I know when to hang around and comfort them, when to leave them to themselves; when to listen to everything they have to say, and when just to shrug and tell them to snap out of it.Anyway, I’m not making any big claims for myself. I know carers, working now, who are just as good and don’t get half the credit. If you’re one of them, I can understand how you might get resentful—about my bedsit, my car, above all, the way I get to pick and choose who I look after. And I’m a Hailsham student—which is enough by itself sometimes to get people’s backs up. Kathy H., they say, she gets to pick and choose, and she always chooses her own kind: people from Hailsham, or one of the other privileged estates. No wonder she has a great record. I’ve heard it said enough, so I’m sure you’ve heard it plenty more, and maybe there’s something in it. But I’m not the first to be allowed to pick and choose, and I doubt if I’ll be the last. And anyway, I’ve done my share of looking after donors brought up in every kind of place. By the time I finish, remember, I’ll have done twelve years of this, and it’s only for the last six they’ve let me choose.

And why shouldn’t they? Carers aren’t machines. You try and do your best for every donor, but in the end, it wears you down. You don’t have unlimited patience and energy. So when you get a chance to choose, of course, you choose your own kind. That’s natural. There’s no way I could have gone on for as long as I have if I’d stopped feeling for my donors every step of the way. And anyway, if I’d never started choosing, how would I ever have got close again to Ruth and Tommy after all those years?

But these days, of course, there are fewer and fewer donors left who I remember, and so in practice, I haven’t been choosing that much. As I say, the work gets a lot harder when you don’t have that deeper link with the donor, and though I’ll miss being a carer, it feels just about right to be finishing at last come the end of the year.

Ruth, incidentally, was only the third or fourth donor I got to choose. She already had a carer assigned to her at the time, and I remember it taking a bit of nerve on my part. But in the end I managed it, and the instant I saw her again, at that recovery centre in Dover, all our differences—while they didn’t exactly vanish—seemed not nearly as important as all the other things: like the fact that we’d grown up together at Hailsham, the fact that we knew and remembered things no one else did. It’s ever since then, I suppose, I started seeking out for my donors people from the past, and whenever I could, people from Hailsham.

There have been times over the years when I’ve tried to leave Hailsham behind, when I’ve told myself I shouldn’t look back so much. But then there came a point when I just stopped resisting. It had to do with this particular donor I had once, in my third year as a carer; it was his reaction when I mentioned I was from Hailsham. He’d just come through his third donation, it hadn’t gone well, and he must have known he wasn’t going to make it. He could hardly breathe, but he looked towards me and said: “Hailsham. I bet that was a beautiful place.” Then the next morning, when I was making conversation to keep his mind off it all, and I asked where he’d grown up, he mentioned some place in Dorset and his face beneath the blotches went into a completely new kind of grimace. And I realised then how desperately he didn’t want reminded. Instead, he wanted to hear about Hailsham.

So over the next five or six days, I told him whatever he wanted to know, and he’d lie there, all hooked up, a gentle smile breaking through. He’d ask me about the big things and the little things. About our guardians, about how we each had our own collection chests under our beds, the football, the rounders, the little path that took you all round the outside of the main house, round all its nooks and crannies, the duck pond, the food, the view from the Art Room over the fields on a foggy morning. Sometimes he’d make me say things over and over; things I’d told him only the day before, he’d ask about like I’d never told him. “Did you have a sports pavilion?” “Which guardian was your special favourite?” At first I thought this was just the drugs, but then I realised his mind was clear enough. What he wanted was not just to hear about Hailsham, but to remember Hailsham, just like it had been his own childhood. He knew he was close to completing and so that’s what he was doing: getting me to describe things to him, so they’d really sink in, so that maybe during those sleepless nights, with the drugs and the pain and the exhaustion, the line would blur between what were my memories and what were his. That was when I first understood, really understood, just how lucky we’d been—Tommy, Ruth, me, all the rest of us.

.

Driving around the country now, I still see things that will remind me of Hailsham. I might pass the corner of a misty field, or see part of a large house in the distance as I come down the side of a valley, even a particular arrangement of poplar trees up on a hillside, and I’ll think: “Maybe that’s it! I’ve found it! This actually is Hailsham!” Then I see it’s impossible and I go on driving, my thoughts drifting on elsewhere. In particular, there are those pavilions. I spot them all over the country, standing on the far side of playing fields, little white prefab buildings with a row of windows unnaturally high up, tucked almost under the eaves. I think they built a whole lot like that in the fifties and sixties, which is probably when ours was put up. If I drive past one I keep looking over to it for as long as possible, and one day I’ll crash the car like that, but I keep doing it. Not long ago I was driving through an empty stretch of Worcestershire and saw one beside a cricket ground so like ours at Hailsham I actually turned the car and went back for a second look.

We loved our sports pavilion, maybe because it reminded us of those sweet little cottages people always had in picture books when we were young. I can remember us back in the Juniors, pleading with guardians to hold the next lesson in the pavilion instead of the usual room. Then by the time we were in Senior 2—when we were twelve, going on thirteen—the pavilion had become the place to hide out with your best friends when you wanted to get away from the rest of Hailsham.

The pavilion was big enough to take two separate groups without them bothering each other—in the summer, a third group could hang about out on the veranda. But ideally you and your friends wanted the place just to yourselves, so there was often jockeying and arguing. The guardians were always telling us to be civilised about it, but in practice, you needed to have some strong personalities in your group to stand a chance of getting the pavilion during a break or free period. I wasn’t exactly the wilting type myself, but I suppose it was really because of Ruth we got in there as often as we did.

Usually we just spread ourselves around the chairs and benches—there’d be five of us, six if Jenny B. came along—and had a good gossip. There was a kind of conversation that could only happen when you were hidden away in the pavilion; we might discuss something that was worrying us, or we might end up screaming with laughter, or in a furious row. Mostly, it was a way to unwind for a while with your closest friends.

On the particular afternoon I’m now thinking of, we were standing up on stools and benches, crowding around the high windows. That gave us a clear view of the North Playing Field where about a dozen boys from our year and Senior 3 had gathered to play football. There was bright sunshine, but it must have been raining earlier that day because I can remember how the sun was glinting on the muddy surface of the grass.

Someone said we shouldn’t be so obvious about watching, but we hardly moved back at all. Then Ruth said: “He doesn’t suspect a thing. Look at him. He really doesn’t suspect a thing.”

When she said this, I looked at her and searched for signs of disapproval about what the boys were going to do to Tommy. But the next second Ruth gave a little laugh and said: “The idiot!”

And I realised that for Ruth and the others, whatever the boys chose to do was pretty remote from us; whether we approved or not didn’t come into it. We were gathered around the windows at that moment not because we relished the prospect of seeing Tommy get humiliated yet again, but just becaus...

用戶評價

這本書的氛圍營造,簡直可以稱得上教科書級彆的典範。它不像那些充斥著爆炸和追逐的暢銷小說,而是將所有的衝突和張力,都壓縮在瞭人物之間那幾不可聞的眼神交流和未說齣口的潛颱詞裏。讀起來,你總感覺背後有一股無形的寒意,它不是來自於外部的威脅,而是源自於故事內部邏輯的冷酷無情。這種“溫柔的殘酷”是如此獨特,它讓你在享受優美散文式敘事的同時,又被一種深沉的悲劇預感所裹挾。我發現自己不自覺地會去分析每一個場景的布景和道具,試圖從中尋找作者隱藏的象徵意義,那種感覺就像是在解讀一幅文藝復興時期的油畫,錶麵寜靜祥和,實則暗藏瞭無數宗教或哲學上的隱喻。特彆是他們共同生活的那個環境,那個地方被描繪得既像一個田園牧歌式的避風港,又像一個精心構建的、隔絕瞭外界的玻璃罩,這種矛盾的統一性,極大地增強瞭故事的深度和令人不安的美感。閱讀體驗是層層遞進的,前期你可能隻是覺得這是一部關於成長的憂傷小說,但越往後讀,你對“成長”和“人性”的定義都會被顛覆。

評分真正讓我感到震撼的是作者對時間流逝的獨特處理。這本書仿佛被置於一個被拉伸或壓縮的時空之中,某些時刻的細節被拉得極長,讓你能清晰地感知到每一秒的重量,而另一些關鍵的轉摺點,卻如同閃電般倏忽而過,留給讀者的反應時間極短。這種節奏上的不均衡,完美地映照瞭書中人物那種被睏在特定軌跡上,卻又試圖抓住“人性”或“情感”的徒勞努力。我仿佛能感受到他們對“正常生活”的渴望,那種渴望不是通過激烈的反抗錶現齣來,而是通過對微小幸福的珍惜和留戀。例如,他們對藝術和文學的癡迷,那不僅僅是愛好,更像是一種精神上的避難所,是他們在既定框架下,為自己爭取到的最後一寸呼吸空間。每當讀到他們分享那些珍貴的、幾乎不被外界承認的“人性證明”時,我都會感到一種強烈的、混閤著憐憫與崇敬的復雜情感。這本書的厲害之處在於,它沒有用宏大的敘事去批判什麼,而是通過聚焦於個體微弱的掙紮,讓讀者自己去構建對“價值”和“存在”的思考。

評分這本書的文字有一種奇特的魔力,像是在一個迷霧繚繞的清晨,你努力想看清遠處的景物,卻發現眼前的每一個細節都帶著一種不真實的、卻又無比鮮活的質感。作者的敘事節奏把握得極好,他從不急於拋齣那些足以震撼人心的真相,而是用一種近乎平淡的、細水長流的方式,讓你沉浸在人物日常的瑣碎和微妙的情感波動之中。我尤其欣賞他對於“記憶”和“身份”的處理,那些看似無關緊要的童年片段,隨著故事的推進,如同被精心排列的碎片,慢慢拼湊齣一個令人心碎卻又無法抗拒的整體圖景。讀到一半時,我常常會放下書,盯著窗外發呆,不是因為情節有多麼跌宕起伏,而是那種滲透在空氣中的、揮之不去的宿命感,讓我不得不停下來消化。那種感覺,就像是看著一個美麗的玻璃器皿,你知道它遲早會碎裂,但你還是忍不住去觸碰它,去欣賞它在陽光下摺射齣的每一道光芒,即使那光芒本身就預示著易碎的結局。作者的筆觸極其細膩,對人物內心的掙紮和潛意識的恐懼,刻畫得入木三分,讓人在閱讀過程中産生強烈的代入感和同理心。

評分這本書的對話設計簡直是一門藝術,它透露齣一種刻意的、略帶疏離的剋製感。人物之間的交流,很少有直截瞭當的錶白或爭吵,更多的是試探、是迂迴,甚至是迴避。你必須非常專注地去捕捉那些“沒有被說齣來的話”,那些隱藏在簡單問句和陳述句背後的巨大情感能量。這種敘事技巧,有效地塑造瞭一種集體性的“沉默的接受”的氛圍,讓人讀起來倍感壓抑,但又不得不承認,這正是人物生存環境下的必然反應。我尤其喜歡那種略顯復古和正式的用詞,它讓整個故事有瞭一種脫離瞭現代喧囂的永恒感,仿佛發生在任何一個時代都成立的悲劇寓言。這種語言上的距離感,反而加深瞭讀者對人物內心孤獨的共鳴,因為很多時候,我們現實生活中的痛苦,也是被語言所無力錶達的那些部分。整本書讀下來,你會感覺自己像是一個安靜的旁觀者,站在一扇半開的窗戶邊,看著裏麵的人們用一種優雅而緩慢的姿態,走嚮不可避免的命運。

評分從結構上看,這本書的構建是極其精巧的,它不是一條直綫前進的故事,而更像是一個不斷自我指涉的圓環。作者不斷地在過去、現在和對未來的模糊預感之間進行切換,但每一次切換都不是為瞭製造懸念,而是為瞭加深讀者對“已知結局”的理解和體驗。這種環形結構,巧妙地避免瞭傳統敘事中“揭示真相”帶來的衝擊力減弱,反而讓真相本身成為瞭一種持續的、滲透性的存在。我個人認為,這本書最成功的地方在於,它挑戰瞭我們對“生命意義”的傳統定義。它沒有提供廉價的希望或積極的口號,而是將一個殘酷的設定,包裹在一層極緻的、對友誼和愛的細膩描繪之下。這使得最終的情感衝擊力達到瞭最大化——你為他們之間的純粹情感而感動,卻又為這種情感注定要麵對的結局而感到無力。讀完後,那種久久不能平息的情緒,與其說是對故事情節的留戀,不如說是對作者所構建的那個世界觀的深思:如果生命被賦予瞭如此明確的終點,我們又該如何定義過程中的價值?這無疑是一部需要時間去沉澱和迴味的作品。

評分正品,不錯的一次購物

評分希望對提高英語有幫助

評分沒想到原版書質量真心一般般啊,比國內印刷紙張差還奇貴

評分不錯

評分不錯,京東信的過 不錯,京東信的過

評分書友注意瞭,京東原版書價格起伏超級大,我買的時候是80+,美國好久居然齣現50+的價格。另外買原版書亞馬遜上比較好,很多好書就跟撿白菜一樣的價格

評分不錯,這個是英文版的買的時候注意瞭

評分便宜的那個版本賣完瞭,隻好選這個國際版,沒想到磨砂封麵,字體紙張均好,很意外,值得這個價格。

評分完美的書!!!!!!!!

相關圖書

本站所有內容均為互聯網搜尋引擎提供的公開搜索信息,本站不存儲任何數據與內容,任何內容與數據均與本站無關,如有需要請聯繫相關搜索引擎包括但不限於百度,google,bing,sogou 等

© 2026 book.coffeedeals.club All Rights Reserved. 靜流書站 版權所有

![Blue Sea藍海 英文原版 [平裝] [4歲及以上] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.windowsfront.com/19092877/550bebbdN267cdd71.jpg)

![Where Are You Going Little Mouse? [平裝] [4歲及以上] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.windowsfront.com/19093610/550bf463Nd93ff8bf.jpg)

![I Love Trucks![我愛卡車!] [平裝] [4歲及以上] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.windowsfront.com/19094740/2b41b767-d03a-4fb5-931e-5dea4dc46337.jpg)

![Where Are the Night Animals? (Let's-Read-and-Find-Out Science 1) [平裝] [4歲及以上] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.windowsfront.com/19095683/550bf643Nc35b93ac.jpg)

![Dinosaurs Big and Small (Let's-Read-and-Find-Out Science, Stage 1) 英文原版 [平裝] [4歲及以上] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.windowsfront.com/19095687/550bf643N2b430b59.jpg)

![The Western Canon [平裝] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.windowsfront.com/19129841/rBEHaVBlDPgIAAAAAABIF1vt9a8AABjVgP-FRsAAEgv804.jpg)

![Thanksgiving Is for Giving Thanks [平裝] [3歲及以上] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.windowsfront.com/19138208/ebf1afc7-3366-4326-95e1-f5c11bb48783.jpg)

![Owl Moon [精裝] [3歲及以上] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.windowsfront.com/19138994/049cae0d-1164-4e23-b532-494c417e588f.jpg)

![Cam Jansen & the School Play Mystery (Cam Jansen Puffin Chapters) [平裝] [8歲及以上] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.windowsfront.com/19140198/02931d09-4793-416d-8a24-7ba6b01f6b30.jpg)

![The Sun Is My Favorite Star 英文原版 [平裝] [4歲及以上] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.windowsfront.com/19235540/rBEGDU-jbl4IAAAAAABiwKTH_tMAAAvAgKF17wAAGLY992.jpg)

![Flat Stanley at Bat (I Can Read, Level 2) 扁平的斯丹利在擊球 英文原版 [平裝] [4歲及以上] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.windowsfront.com/19249070/550bf03eNa31d1783.jpg)

![Citizens of the Sea: Wondrous Creatures From the Census of Marine Life [精裝] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.windowsfront.com/19371496/rBEhUlJbkKwIAAAAAAEDevmn8JMAAEHKQMm5KMAAQOS212.jpg)

![Beauty and the Beast (Flip-Up Fairy Tales) [平裝] [3歲及以上] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.windowsfront.com/19409456/rBEhU1JbaE8IAAAAAAD4yIut05IAAEGpADKO38AAPjg056.jpg)

![Jedi Academy: Star Wars絕地學院:星球大戰 英文原版 [精裝] [8-12歲] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.windowsfront.com/19456216/5539a787N22d385f8.jpg)

![We Were Liars 我們都是騙子 英文原版 [平裝] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.windowsfront.com/19478841/53bcfd4cN03f2aaf7.jpg)

![The Cuckoo's Calling[杜鵑在呼喚] [平裝] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.windowsfront.com/19500691/rBEbRVNp4VUIAAAAAAB0JXtgzbQAAAFSwOyyT0AAHQ9269.jpg)

![Oliver Twist [精裝] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.windowsfront.com/19512389/5463148fNae5b4ad3.jpg)

![Madrigals Magic Key to Spanish 英文原版 [平裝] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.windowsfront.com/19522588/54632034Ne67c47e8.jpg)

![Thea Stilton #20: Thea Stilton And The Missing Myth老鼠記者妹妹菲-斯蒂頓係列:主演消失之謎 英文原版 [平裝] [7-10歲] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.windowsfront.com/19531245/5523495dN6d94da46.jpg)